At a Glance

Sharing a single learned policy across many cooperative agents causes teamwork to collapse as agents explore; splitting policies into groups or giving the shared model signals about learning progress can delay or prevent that collapse.

ON THIS PAGE

What They Found

Cooperation steadily falls as agents explore more and the cost of being exploited grows; shared-policy learning finds stable solutions that favor defection rather than unstable training. The collapse maps to changes inside the shared network: cooperative and defective behaviors become mixed in its internal representations and the difference in estimated value between the two actions shrinks toward zero. Giving the shared network extra signals about exploration or training progress, or limiting parameter sharing to smaller groups, preserves cooperation over a much wider range of exploration strengths. Network layout matters too: local spatial structure helps sustain cooperation, while globally mixed interaction patterns make collapse worse. Guardrails Pattern

Data Highlights

1Shared-policy collapse thresholds were identified at specific cooperation cutoffs: shared DQN threshold found at cooperation = 0.55, while grouped DQN’s threshold (with 10 groups) sits near cooperation = 0.15 and shows partial recovery at high exploration.

2Action-value gap (the average difference in learned value between cooperate and defect) decreases monotonically toward zero as exploration strength increases (evaluated at temptation D_r = 0.25; statistics averaged over 30 random seeds).

3Collapse behavior is robust to population size: grid runs at 30×30, 40×40 and 50×50 show nearly aligned cooperation-vs-exploration curves, indicating the phenomenon is not a finite-size artifact.

What This Means

Engineers building multi-agent systems that rely on a single shared model should be cautious: shared representations can silently erode cooperation when agents explore. Technical leads and reliability teams evaluating agent-to-agent interactions should consider grouped policies or observability signals as practical mitigations. Researchers studying multi-agent trust and failure modes will find the internal-representation diagnosis useful for designing more robust architectures and tests. Consensus-Based Decision Pattern

Not sure where to start?Get personalized recommendations

Key Figures

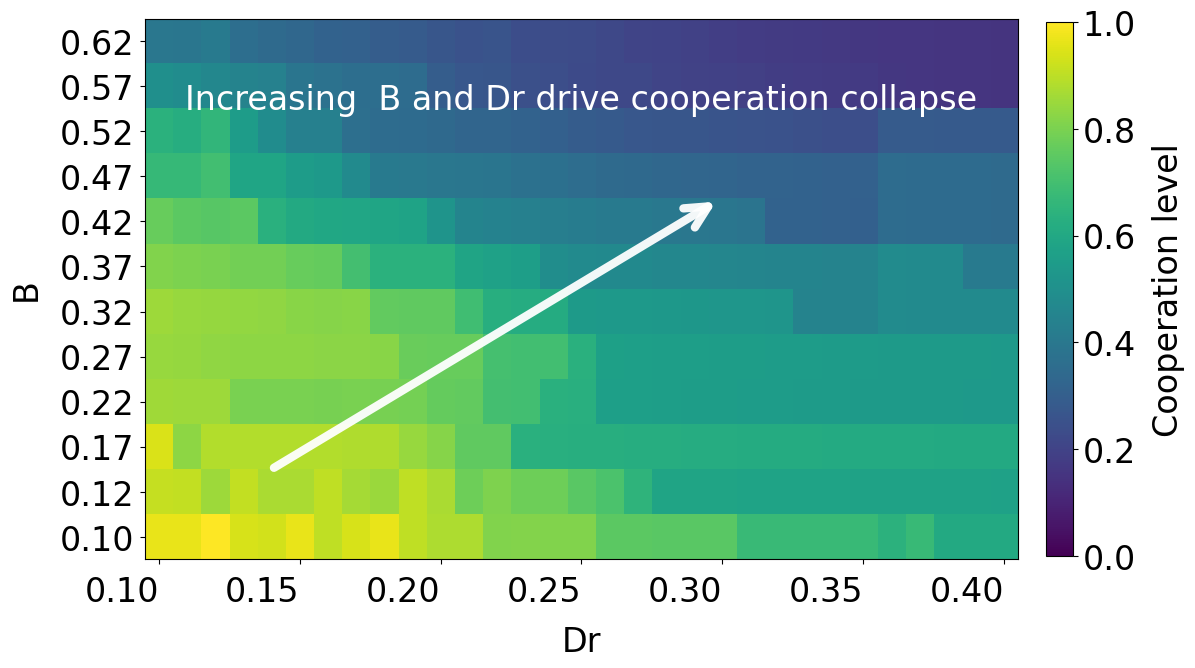

Fig 1: Figure 1: Cooperation levels in shared-policy DQN as a function of exploration strength B B and payoff harshness D r D_{r} . Each cell is the mean over 30 random seeds during evaluation. Cooperation degrades systematically as either parameter increases, forming an extended low-cooperation region in the upper-right. The smooth boundaries indicate structured collapse rather than sporadic failures.

![Figure 2: Collapse thresholds D r ∗ ( B ) D_{r}^{*}(B) as a function of exploration strength B B (mean over 30 seeds). (a) Shared DQN: all agents use one network. Threshold decreases monotonically with B B (identified at cooperation = 0.55). (b) Grouped DQN: 10 groups of 90 agents, each with independent network. Threshold shows non-monotonic dependence with partial recovery at high B B (identified at cooperation = 0.15). Different thresholds reflect different baseline cooperation levels. Dashed lines mark tested D r D_{r} range [ 0.10 , 0.40 ] [0.10,0.40] . Hollow markers indicate threshold outside tested range.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.05509v1/Figure_2_-_Shared_vs_Group.png)

Fig 2: Figure 2: Collapse thresholds D r ∗ ( B ) D_{r}^{*}(B) as a function of exploration strength B B (mean over 30 seeds). (a) Shared DQN: all agents use one network. Threshold decreases monotonically with B B (identified at cooperation = 0.55). (b) Grouped DQN: 10 groups of 90 agents, each with independent network. Threshold shows non-monotonic dependence with partial recovery at high B B (identified at cooperation = 0.15). Different thresholds reflect different baseline cooperation levels. Dashed lines mark tested D r D_{r} range [ 0.10 , 0.40 ] [0.10,0.40] . Hollow markers indicate threshold outside tested range.

Fig 3: Figure 3: Effect of state augmentation on cooperation outcomes in shared-policy DQN under varying exploration strength B B . All curves show mean cooperation levels averaged over 30 independent random seeds. The baseline curve corresponds to the original shared DQN, whose state encodes only local interaction information, consisting of each agent’s own recent action together with the recent actions of its neighbors. We compare this baseline against augmented variants that append additional scalar signals to the original state vector: a temporal exploration signal τ \tau , a coarse training-progress (annealing) indicator, and their joint inclusion. All configurations employ identical learning algorithms, network architectures, reward structures, and interaction topologies; only the information available to the shared value function differs. Joint augmentation yields the most robust behavior relative to the baseline, exhibiting a stable and weakly increasing cooperation trend as exploration strength B B increases, while substantially reducing sensitivity to exploration-induced degradation. In contrast, single-signal augmentation produces more limited and regime-dependent effects.

Fig 4: Figure 4: Visualization of hidden-layer representations learned by the shared-policy DQN under increasing exploration strength B B . Each panel shows a two-dimensional UMAP projection of hidden activations corresponding to agents’ states, with points colored by the selected action (cooperate or defect). At low exploration, cooperative and defective actions occupy partially distinct regions in the projected latent space. At intermediate B B , the representations exhibit increased geometric clusterability, while under strong exploration the latent space becomes increasingly diffuse, with cooperative representations shrinking and losing stability. Silhouette scores, computed from unsupervised two-cluster partitioning of the hidden representations, quantify this non-monotonic evolution in cluster structure. Importantly, silhouette scores reflect geometric clusterability rather than action-discriminative separability, and their transient increase at intermediate B B does not correspond to improved support for cooperative decision-making.

Ready to evaluate your AI agents?

Learn how ReputAgent helps teams build trustworthy AI through systematic evaluation.

Learn MoreYes, But...

Experiments use a controlled dynamic Prisoner’s Dilemma and value-based deep Q-learning; results may differ for other games, reward structures, or learning algorithms. State augmentation and grouping help but require domain knowledge to choose useful signals or sensible groups. Topology tests were limited to fixed-degree networks and a few graph families, so real-world interaction graphs could produce different behavior. Tree of Thoughts Pattern

Methodology & More

A network of agents played repeated local Prisoner’s Dilemma games while all agents learned from a single shared value network (a shared Deep Q-Network). Exploration strength and payoff harshness were varied to map when cooperation emerges or collapses. Across 30 random seeds per condition, cooperation fell smoothly as exploration or the cost of being exploited increased; the system converged reliably but to low-cooperation outcomes rather than failing to converge. Probing the shared network showed cooperative and defective behaviors became entangled in hidden-layer representations and the action-value gap (difference in estimated value between cooperating and defecting) shrank toward zero as exploration rose. Two practical fixes improved robustness. First, grouped policy learning—where agents are split into subsets that each use their own network—shifted the collapse boundary and often preserved cooperation longer. Second, augmenting the state fed into the shared network with simple scalar signals (a coarse training-progress indicator and an exploration signal) delayed or partially reversed collapse, making cooperation more stable across exploration levels. Spatially local interaction graphs (grid-like) also helped preserve cooperation, while globally mixed networks were more vulnerable. The takeaway: shared parameter designs are efficient but can hide a structural failure mode; improving observability of learning dynamics or reducing representation sharing are effective countermeasures. Memory Poisoning Semantic Capability Matching Pattern

Avoid common pitfallsLearn what failures to watch for

Credibility Assessment:

Authors have very low h-indices and no affiliation/venue signals; arXiv preprint with no citations.