In Brief

Actively choosing which tasks and head-to-head comparisons to run finds the top agents far faster than blindly scoring everything; simple methods often work well early, but the best method depends on how varied the tasks are and whether the data is synthetic or real-world.

ON THIS PAGE

Key Findings

Active evaluation—where the evaluator picks which task and which two agents to compare each round—Active evaluation can drive top-3 identification error to zero within a few thousand samples in synthetic settings. Simple baselines like uniform averaging and a bandit-style upper-confidence method perform surprisingly well early on, while batch Elo ratings are reliable when tasks are similar. For real-world Atari data, ranking methods based on a smooth ranking objective (Soft Condorcet Optimization) outperformed BatchElo by roughly two times, showing domain matters.

Data Highlights

1Top-3 identification error fell to zero within ~2,000 iterations for several algorithms on synthetic data (m=8 agents, n=50 tasks).

2UniformAveraging reduced error fastest in the first 1,000 iterations in 3 of 4 synthetic settings, with BasicUCB showing comparable early performance.

3On the Atari agent dataset, SCO-based methods beat BatchElo by about two-fold in ranking error; BatchElo was strongest in low task variation (phi=0.3) scenarios.

Implications

Engineers building or deploying multiple AI agents who need a fast, cost-effective way to pick the best model should care—Guardrails Pattern active evaluation cuts the number of comparisons required. Technical leads and evaluation teams deciding how to budget large-scale testing will get the most value by matching the selection method to task variability: use BatchElo-like aggregation when tasks are similar, but prefer Semantic Capability Matching Pattern SCO-style ranking for diverse, real-world tasks.

Explore evaluation patternsSee how to apply these findings

Key Figures

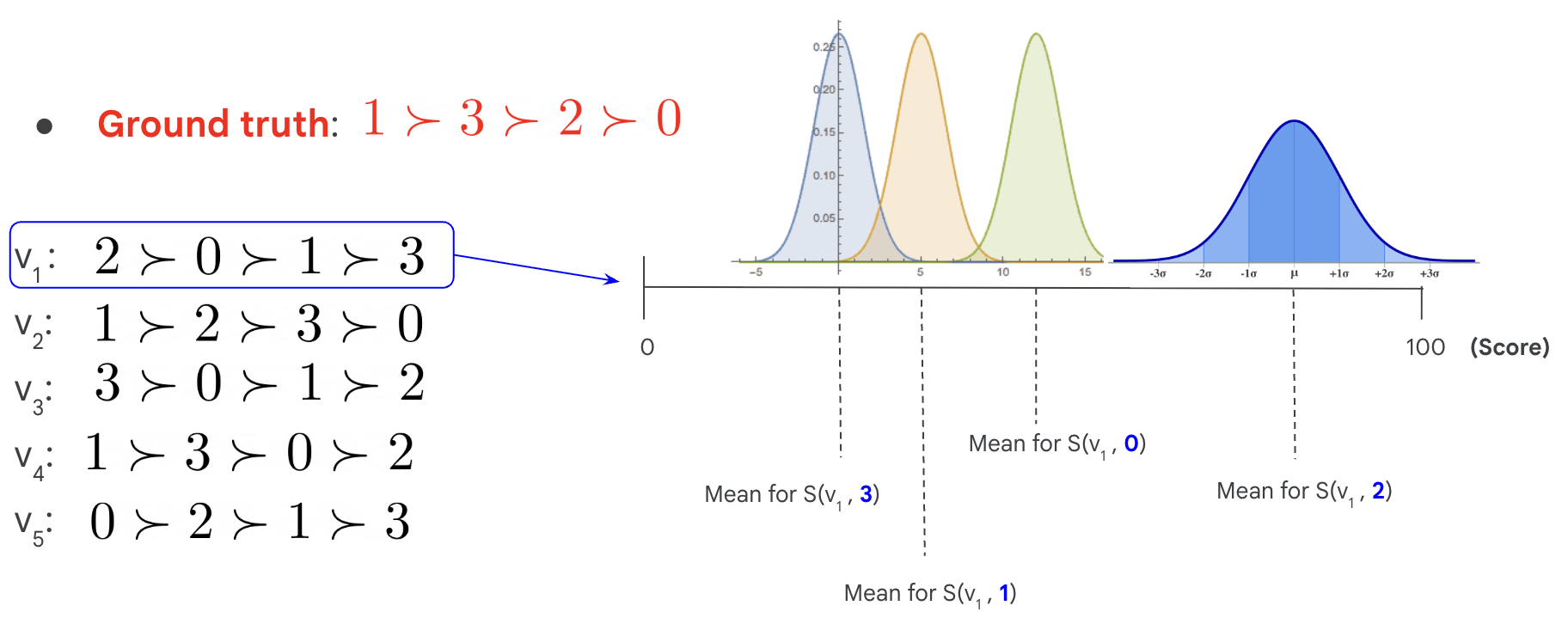

Fig 1: Figure 1. Example of synthetic data generation process with m = 4 m=4 and n = 5 n=5 . The task rankings ( ≻ v 1 ∗ , ≻ v 2 ∗ , ⋯ , ≻ v 5 ∗ ) (\succ^{*}_{v_{1}},\succ^{*}_{v_{2}},\cdots,\succ^{*}_{v_{5}}) have Kendall-tau distances 4, 1, 4, 1, and 5, respectively, from ≻ ∗ \succ^{*} .

Fig 2: Figure 2. Exp Condition 1: Generalized top- k k ranking error (GRE) over iterations for several algorithms. Each line is a mean over the same 100 seeds with 95% confidence intervals in shaded area. Each data point is a sliding-window average of the most recent 250 values of GRE for the reported ranking ≻ t \succ^{t} at iteration t t . The top two graphs use dispersion ϕ = 0.3 \phi=0.3 , with k ∈ { 3 , 8 } k\in\{3,8\} , where k = 8 k=8 corresponds to normalized Kendall-tau distance. The bottom two use ϕ = 0.6 \phi=0.6 and vary k k similarly.

Fig 3: Figure 3. Exp Condition 2: Generalized top- k k ranking error (GRE) over iterations for several algorithms. Each data point is a sliding-window average of the most recent 250 values of GRE for the reported ranking ≻ t \succ^{t} at iteration t t . Both graphs use k = 3 k=3 . Please note the log scale for both axes.

Fig 4: Figure 4. Task variation for samples from a Mallows model with m = 8 , n = 50 m=8,n=50 . Each graph shows a histogram of the 50 Kendall-tau distances between the task ranking and the ground truth ranking, K d ( ≻ ∗ , ≻ v ∗ ) K_{d}(\succ^{*},\succ^{*}_{v}) .

Ready to evaluate your AI agents?

Learn how ReputAgent helps teams build trustworthy AI through systematic evaluation.

Learn MoreYes, But...

Results depend heavily on how tasks vary: some algorithms overfit when the task selector is adversarial and can prefer rare, unrepresentative tasks. Synthetic experiments used 8 agents and 50 tasks—real deployments with many more agents or different score noise may shift which method is best. The study compares several practical baselines but does not provide formal sample-complexity guarantees or cost models tied to human labeling or raters. Context drift in adversarial settings can exacerbate these issues [ /failures/context-drift ].

Methodology & More

Active evaluation reframes multi-task benchmarking so the evaluator chooses which task and which pair of agents to compare on each round. The paper introduces a single efficiency objective—Average Generalized Ranking Error (AGRE)—which blends two needs: correctly identifying the top-k agents and getting their internal ranking right. Algorithms compared include simple baselines (uniform task sampling + average scores), Elo-style rating (batch and online), a bandit-style Upper Confidence Bound on agents, game-theoretic Nash averaging, proportional representative sampling, and ranking-based methods like Soft Condorcet Optimization (SCO) Soft Condorcet Optimization (SCO). Experiments used two synthetic data generators (e.g., Mallows/Plackett-Luce style noise) and an incremental replay of Atari agent scores (m=8, n≈50–57).

Avoid common pitfallsLearn what failures to watch for

Credibility Assessment:

Authors include some recognized names (Marc Lanctot) but overall low h-indices and no strong institutional listing; arXiv preprint.